U.S. Military Steins*

By Louis Foster

Since 1945 the United States has maintained a military presence in Europe, especially Germany. Immediately after the end of hostilities, the Army of Occupation was charged with keeping peace and civil order and restoring Germany.

Many people were involved in this mission, including military figures such as General Lucius Clay who was the U.S. Governor of the American Zone, which ranged from just north of Frankfurt to the Swiss and Czechoslovakian borders and included a portion of Berlin. General Clay’s contributions included ordering and directing the Berlin Airlift, which resulted in half of Berlin remaining free of Russian control during the Cold War. Another important figure was General of the Army George Marshall who served as United States Secretary of State under President Truman. General Marshall was awarded the Nobel Peace prize for his efforts to finance the rebuilding of war-ravaged Europe through the Marshall Plan. This resulted in the economic “miracle” which enabled West Germany to recover from the devastation of the war and, ultimately, the reunification of the country after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989. Germany today owes a great debt to the wisdom of General Marshall. Thanks to him, the mistakes following World War One were not repeated.

| | Figure 1 |

|

| | Figure 2 |

|

| | Figure 3 |

|

| | Figure 4 |

|

The military role changed from being an Army of Occupation to being an ally when civilian government was reestablished in West Germany under a new government formed in Bonn in 1949. For over half a century the troops of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have been stationed in Western Europe to prevent another world war. The bulk of these soldiers served in Germany (President Charles deGaulle had NATO forces withdrawn from France in 1967) and today approximately 85,000 American service personnel are stationed in Europe, the majority in Germany.

One of the customs followed by these troops is that of the Kaiser’s soldiers of purchasing a personalized beer stein to commemorate their military tour of duty. As these men (and women) retire or die, their steins are finding their way into the market and are frequently seen in commercial stein auctions. While they are not as attractive as the ones of eighty to one hundred years ago, they are not as highly sought after nor as expensive either ($40 – $150). What the future holds is uncertain, but it is a good bet that they will come into their own someday.

| | Figure 5 |

|

| | Figure 6 |

|

| | Figure 7 |

|

| | Figure 8 |

|

The U.S. regimentals have many common characteristics with the originals and many differences. First, the body itself. To my knowledge, all the new ones are made of porcelain, not pottery or salt-glazed stoneware as many of the originals were. The majority of them have a risqué lithophane of a seminude woman, the bodies tend to flare out near the bottom, and the handles have a “lump” on the inside. In short, almost everything that distinguishes a reproduction regimental from an original is present on the U.S. military steins. I have never seen a U.S. military regimental with a roster and they seldom, if ever, have any hand-painted decorative work to enhance the details.

On the other hand, the finials are often specialized to the unit, i.e. a soldier for an infantry unit, a tank for an armored unit, a castle for an engineering unit, a cannon for an artillery unit, and so forth. The decorations or side panels usually do not depict scenes from garrison or field duty but consist mainly of regimental insignia, crests or division patches. Often the thumblift is a U.S. eagle holding olive branches (peace) and arrows (war) in its talons, a banner in its beak and a shield with a field of stars over its head.

| | Figure 9 |

|

| | Figure 10 |

|

| | Figure 11 |

|

| | Figure 12 |

|

Many, but not all, include the owner’s name and rank and the dates he or she served. Also frequently found on the stein is the town or Kaserne (post) where the owner was stationed. One big difference is that it is not unusual to find one of those steins which belonged to a senior non-commissioned officer or an officer. This, of course, would be unheard of with the Imperial regimentals which were purchased almost solely by reservists who were the lowest ranked soldiers and served only two or three years.

At this time, the market is not defined but it is unlikely that the same things which make the older regimentals more desirable and expensive will affect the price of the post World War II U.S. steins. There are no longer Luttschiffe (dirigibles or airships similar to blimps) in military service, Eisenbahn (railroad) units do not exist and a medic’s stein does not excite me in the least. Tanks, the 1940s replacement for horse mounted units, strike me as the most attractive and desirable with airplanes, missile and artillery units following. Unfortunately, the common infantry (foot soldier) steins probably will not move up in status. Finally, I am not aware of any U.S. service steins belonging to sailors, but cannot rule out this possibility.

There is evidence that one interesting development in U.S. Army military steins did take place between the early 1950s and the 1970s. Two of my earliest steins list the World War II campaigns in which the soldier’s unit participated, but this detail has disappeared from later steins, making them both simpler and less interesting. This change is probably the result of the passage of time and the diminished lack of importance attached to old battles. To paraphrase General Douglas MacArthur, “old soldiers never die, they just fade away,” but as they fade away, their military steins will go on.

| | Figure 13 |

|

| | Figure 14 |

|

| | Figure 15 |

|

| | Figure 16 |

|

I have seen mugs naming units which served in Korea but have seen nothing from Viet Nam or the Gulf War. Perhaps they do exist but are still in the possession of their original owners. One question which I was asked recently but could not answer relates to the West German Army which was organized in the 1950s. Did those soldiers purchase regimental steins like their grandfathers did before the First World War or is this a tradition which only the Americans have continued?

**********

Figure Descriptions

Figure 1: Stein named to Lt. Louis C. Wagner, stationed in Munich from 1955-1958.

Figure 2: Armored officer’s insignia showing that Lt. Wagner was assigned to the 68th Armored Regiment.

Figure 3: Lt. Wagner’s unit was part of the 11th Airborne and his “jump” wings are included in the decoration of his stein. Note that the U.S. Army M-48 (Patton) tank is the finial and that the thumblift is a lion holding a Bavarian shield.

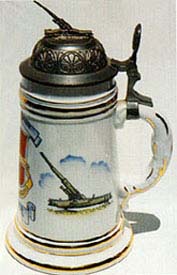

Figure 4: Stein of an Artillery unit equipped with one of a small number of atomic cannons deployed in Germany from about 1953 until 1962 (finial and side scene).

Figures 5-8: Stein named to PFC John H. Brown, who served with the 519th Artillery Battalion from 1952 to 1954. The finial is a 105mm howitzer (barrel is bent). The many side scenes show various activities in the field, including forward observers in an airplane; others using a periscope, sighting the guns; fire direction control personnel computing the distance and direction to a target; a mess or field kitchen truck; and soldiers stringing communications wires for field telephones. A band around the top lists campaigns in Naples, Foggia, Rome, the Arno, Southern France, Rhineland, Central Europe, Ardennes and Alsace. The rear of the stein shows the unit’s military and German connections. This battalion was part of the 36th Field Artillery, which was part of the Fifth Corps, which was one of two corps forming the 7th U.S. Army. The unit was stationed in Germany, in Hessen at Babenhausen.

Figure 9: Stein named to Sgt. Charles Tice, Heavy Mortar Company, stationed at Warner Kaserne in Munich in 1952. Sgt. Tice was part of the 172nd Infantry Division. Warner Kaserne was a six-story troop barracks built in the 1930 for Wehrmacht SS units. It was capable of housing approximately 2,000 soldiers. This post was used to shelter displaced persons and refugees immediately after the end of World War II, and by 1950 was the post for four U.S. Army battalions. In the late 1970s, it was returned to the German Army. This stein is unusual because the lid was made from a mold for a pre WWI Imperial German mounted unit but has a thumblift depicting a U.S. Army eagle.

Figuree 10: Stein named to Master Sergeant Charles S. Patrick, Company A, 13th Armored Infantry Battalion, Third Armored Division, stationed in Ayers Kaserne, Kirchgoens, West Germany in 1956. The finial is an M-113 armored personnel carrier which was introduced in the early 1950s to move an infantry squad (approximately 10 soldiers) quickly and safely into combat.

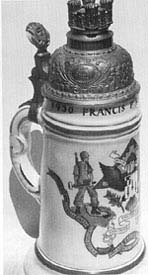

Figures 11-13: Stein named to Francis P. Koisch, who served from 1950 to 1953 and was assigned to the 54th Combat Engineer Battalion, part of the 7th U.S. Army. The stein lists the unit’s World War II campaigns. The filial is the castle symbol of the U.S. Army Engineer Corps. Side scenes portray engineers constructing a bridge and carrying equipment to detonate a demolition charge, typical duties of engineers in a combat situation.

Figure 14: Unnamed stein representing the 5th Missile Battalion, 6th Artillery, stationed in Baumholder. Missiles were under the jurisdiction of the Artillery and the finial is a Nike missile, which was deployed in Europe in the mid-1950s.

Figure 15: U.S. Air Force stein named to “Dean” stationed at Rhein Main Air Base in Frankfurt from 1966-1969 and assigned to the 6916th Security Squadron. The finial is a large four-engine airplane, possibly a C-130 as this is the marking on the bottom.

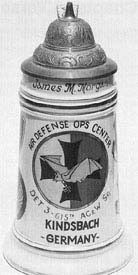

Figure 16: Stein named to James M. Morgan, who was assigned to Detachment 3, 615th AC&W Squadron, Air Defense Operations Center in Kindsbach, West Germany. Morgan was part of the 17th U.S. Air Force. The central figure is a bat wearing an Iron Cross around its neck.

__________

*Reprinted by permission from Prosit, the Journal of Stein Collectors International, Vol 2, No. 23, September 1997

Louis Foster, author of this article, would like to correspond with others who have an interest in U.S. Military steins. His e-mail address is "[email protected]".