Figural Munich Child Steins:

History and Mysteries1,2

by Louis Foster

This article is intended as an adjunct to various manufacturer catalogs in the Beer Stein Library. Clicking on any of the links provided herein will produce a separate window displaying the catalog listing associated with the item cited in the text.

—————————

Munich and the Munich Child

In European terms, Munich is a relatively new city. Unlike many major German cities, it does not predate the Roman occupation nor was it established by the Romans. Rather, it began to develop as a result of its proximity to a bridge over the Isar river, less than 900 years ago. The bridge was important as an access point for transporting salt into the rest of Germany. It also served as a significant revenue source, in that the owner was entitled to collect tolls for the traffic crossing.

Initially, the bridge that performed this function was owned by Bishop Otto von Freising. However, in 1156, the ruler of Bavaria, Duke Henry the Lion, burned the Bishop’s bridge and constructed his own a few miles upstream. Duke Henry’s bridge was near a small community of Benedictine monks called “zu den M�nichen” or “at the site of the little monks,” which eventually gave the city its name and its symbol — a monk.

In 1158, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa intervened in the on-going struggle between the two men. The conflict was finally resolved when the Emperor ordered that one-third of the tolls collected by Duke Henry be paid to the Bishop in restitution for the loss of his bridge.

As the population around the bridge grew, authorization was given for the holding of markets and the minting of coins and, by 1173, walls were built to protect the area’s 2,500 residents. Duke Henry, however, following an act of defiance against the Emperor, was banished from Bavaria in 1180. The Bishop moved quickly to eliminate the new city and to again route traffic through Freising, but his efforts were to prove unsuccessful. The city continued to grow and prosper.

Use of a monk as the city’s symbol can be seen in examples dating back as far as 1239. The city seal shown here, from the Munich “Stadtmuseum” (city museum), is circa 1323. Invariably, these early precursors to the modern Münchner Kind’l were depicted holding a Bible in the left hand and extending the right hand in a gesture of blessing to the viewer. It is not until the 19th century that the monk evolved into the typically female Munich Child we’re familiar with today, often shown holding a beer stein and white radishes which, in Bavaria, were eaten as a snack while drinking beer.

Early Distributors and the Puzzles They Created

Trying to determine who actually made the many different early Munich Child steins can often be extremely difficult and still presents many mysteries that await further research. This is because in late 19th and early 20th century Munich, there existed a group of enterprising merchants who appear to have controlled the marketplace, and may well have played a major role in the creation of what then was a rapidly expanding demand for figural steins. The problem for collectors and researchers today is that these entrepreneurs typically made arrangements to have steins produced by a variety of manufacturers, but with identifying marks of the distributors, or middlemen, rather than with the marks of the manufacturers who actually made the steins.

|  |

In reviewing old advertising material from the 19th century, it is easy to reach the conclusion that these distributors had broad access to retail outlets in Munich and probably throughout Bavaria. One of them, for example, owned a department store, and another is even known to have provided custom-made steins with coffee advertising to be sold in a grocery store. Overall, the Munich distributors appear to have developed strong relationships with many or most of the retailers catering to both tourists and locals, making it quite difficult for outsiders to enter the market. The names best known to American collectors are Jakob Reinemann, Martin Pauson and Josef M. Mayer, but several other players also entered the mix.

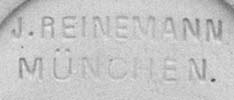

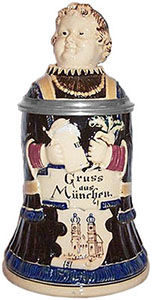

Jakob Reinemann founded his business in 1873 but, only seven years later in 1880, sold it to a merchant named Otto Lowenstein. Reinemann died the following year, but Lowenstein continued to order and sell steins with Reinemann’s name on them for many years thereafter. Munich Child steins bearing the Reinemann name can be found in both pottery (i.e., cream stoneware) and porcelain (below left).

| Pottery (left) and porcelain (right)

Reinemann steins

manufacturer unknown

|

|

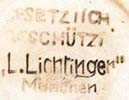

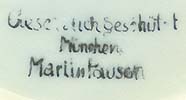

| Reinemann (left)/Lichtinger (right)

painting comparison

Merkelbach & Wick No. 209 |

|

In 1878, Ludwig Lichtinger, opened his business and was later joined by his brother Joseph. In 1896, the Lichtinger firm was also sold to Otto Lowenstein. Figural Munich Child steins marked L. Lichtinger seem to be limited to only one style and are the same form as the majority of the Reinemann Munich Child figurals (i.e., Merkelbach & Wick No. 209). However, the painting styles are clearly distinguishable, as may be seen in the comparison shown above right.

The Martin Pauson firm was established in 1884 and the majority of the Munich Child steins we see today bearing the Pauson name were produced in porcelain by Schierholz & Sohn of Plau, in the German State of Thuringia. All porcelain Munich Child steins bearing the Pauson name feature high-quality lithophanes. Schierholz had a strong reputation as a lithophane maker, and some of the finest examples of this art appear on Munich Child figurals.

One porcelain stein that is sometimes seen with marks of both Pauson and Schierholz depicts a Munich Child in a Barrel. Several other porcelain Munich Child steins bearing the Pauson name have also been identified as Schierholz products based on their physical characteristics, including unnumbered steins designated in the Schierholz catalog as Nos. (X21), (X22), (X23) and (X25), among others.

Typical of Pauson’s steins is the appearance of his name on the pewter shank between the strap attachment on the handle and the hinge which connects it to the lid. This is true whether the stein was made by Schierholz in porcelain, or in pottery, as was the case with Merkelbach No. 564. Note the similarities between that stein and Merkelbach Nos. 323 and 544. Those similarities, of course, provided the link between the Pauson-marked stein and Merkelbach as the manufacturer.

|

Steins with Goldschmidt marks

No. 138 (¼-ltr.) and No. 139 (⅛-ltr.)

manufacturer unknown |

Josef M. Mayer established his business in 1888 and is responsible for two different series of porcelain figural Munich Child steins. Again, based on physical characteristics, these steins are believed to have been made by Schierholz & Sohn, and are designated in the Schierholz catalog as Nos. (X24) and (X25).

There is some evidence that both Pauson and Mayer, in addition to acting as distributors, also had locations in Munich where decorating work and pewter attachments were completed in “finishing shops,” adding further to their grip on the market. These facilities would have provided some cost savings, since it was undoubtedly cheaper and safer for them to ship the steins in pieces, rather than as finished products. It also allowed for some degree of customization, like providing special thumblifts or even adding music boxes that played tunes specified by their customers.

Although not located in Munich, at least one other distribution company appears to have been a competitor in the figural Munich Child stein market, over time using the two marks shown at the right. The first belonged to Jakob Goldschmidt, who was in business in Nuremberg in the 1890s. The second was used after 1906 when his brother Moritz joined the firm to form Gebr�der Goldschmidt (Goldschmidt Brothers).

Like their Munich counterparts, the Goldschmidt Brothers were not manufacturers or, at the very least, did not manufacture the figural Munich Child steins bearing their logos. Rather, they purchased their steins from an as yet unidentified steinmaker based in the Westerwald, examples in both pottery and salt-glazed stoneware may be seen at the left.

The Mystery Molds

While nearly twenty known figural Munich Child steins do not have a currently identified manufacturer, about a third of them have a body style that is quite similar, though not identical, to Merkelbach & Wick No. 209, distributed by Jakob Reinemann. This particular Münchner Kind’l holds a Hofbr�uhaus stein (marked “HB”) in one hand and three white radishes in the other. The Hofbr�uhaus stein is not particularly realistic but, rather, has a relatively flat shape lying flush against the Munich Child’s upper torso. Two of the radishes are held topside up and one is held by the root.

Steins with nearly identical characteristics (but always with different bases) were produced by an unknown manufacturer(s) in both porcelain and blue-gray stoneware, as well as in a mixed form with a porcelain head on a pottery body, all three of which are pictured below. A pottery stein with exactly the same body as the two on the right (all bearing the mold number 117), but with a different head, was shown previously in our discussion of Jakob Reinemann steins (Reinemman example on far left). Moreover, the two Goldschmidt steins (above) also appear to have been designed by the same hand. There’s even a stein with the head shown below but with a completely different stoneware body attributed to Reinhold Hanke.

| | Pottery |

|

| | Stoneware |

|

| | Porcelain/Pottery |

|

Did one of the Munich distributors (perhaps Reinemann) own the molds and contract-out production to several different manufacturers? Did two or more manufacturers engage in a cooperative effort on their own? Are there another possible explanations? We may or may not ever find the answers to these questions, but if some enterprising researcher actually manages to accomplish that objective, one of the major mysteries of figural Munich Child steins will have been resolved.

Some other currently unidentified Munich Child figurals are pictured below. However, other than the fact that they are all based on the same subject-matter, they share few, if any, additional characteristics. As with most other beer stein mysteries, these may remain long-standing questions, but unlike those discussed above, if and when they are resolved, it almost certainly won’t be as a group.

| Porcelain

½-liter

marked 1832 |

|

| Porcelain

½-liter

lithophane |

|

| Porcelain

½-liter

lithophane |

|

| Earthenware

½-liter

unmarked |

|

| Pottery

½-ltr. or ¼-ltr.

unmarked |

|

| Pottery

½-liter

marked J.M. Mayer |

|

Some Final Thoughts

Although beer stein collectors, more often than not, tend to concentrate their efforts on the search for antiques, manufacturers did not stop making figural Munich Child steins after World War I, and they continue to make them today. New examples have recently been produced by contemporary companies such as KING-Werk in the Westerwald, Sandizell in Thuringia, and even Hachiya Brothers in Japan, not to mention Domex in the Westerwald via China, among others. In my view, it is a mistake to overlook these “modern” Münchner Kind’l steins which will, in the not too distant future, become antiques in their own right.

| | KING-Werk |

|

| | Sandizell |

|

| | Hachiya Bros. |

|

| | Domex |

|

Overall, more than fifty figural Munich Child steins may currently be found cataloged by manufacturer in the Beer Stein Library. Of those that are still unidentified, some (perhaps even most) may well have been produced in those very same factories. If examples in your collection hold any clues to resolving the remaining mysteries, please contact me through the Library by email addressed to [email protected]. And of course, as new discoveries are made, BSL members will be among the first to know.

__________

1) This article is dedicated to the late Sam Brainard who sold me my first Munich Child stein in 1978.

2) Editor’s Note: As the title of the article suggests, its focus is mainly on the “mysteries” currently associated with figural Munich Child steins, rather than on the considerable store of information on the subject to be found in the various BSL manufacturer catalogs. For direct access to all cataloged Munich Child steins, simply go to the Library’s search prompt and enter the words “figural munich child”.

© 2001-2026 Beer Stein Library — All rights reserved.